- The Architecture of Behavioral Transformation and the Power of Marginal Gains

- The Neurological Mechanics of the Habit Loop

- First Rule: Make it evident.

- The Second Law: Make it Appealing

- Third Rule: Make It Simple

- The Fourth Law: Make It Fulfill

- Implementation in Life Design and Workplaces

- Taking the Next Step: Your Handbook of Permanent Transformation

The Architecture of Behavioral Transformation and the Power of Marginal Gains

The pursuit of excellence and the modification of human behavior are often misconstrued as the results of singular, monumental shifts or “once-in-a-lifetime” transformations. However, the prevailing evidence in behavioral science, as synthesized in contemporary literature, suggests that significant outcomes are the lagging measures of a system composed of small, incremental adjustments. This philosophy, centered on the concept of “atomic habits,” posits that the fundamental units of remarkable results are regular practices that are small, easy to execute, and yet possess incredible power through the mechanism of compound growth.

The core of this transformative framework lies in the mathematical reality of the “1 percent rule.” If an individual can improve a specific skill or behavior by just 1 percent each day, the cumulative effect over a calendar year is not merely additive but exponential. The compounding interest of self-improvement results in being approximately 37.78 times better after 365 days of consistent growth. Conversely, a 1 percent daily decline leads to a trajectory that approaches zero, illustrating how time serves as a magnifier that multiplies the quality of one’s habits. In the short term, the difference between a slightly better or slightly worse decision is often negligible; however, over a long temporal horizon, these choices determine the gap between success and failure.

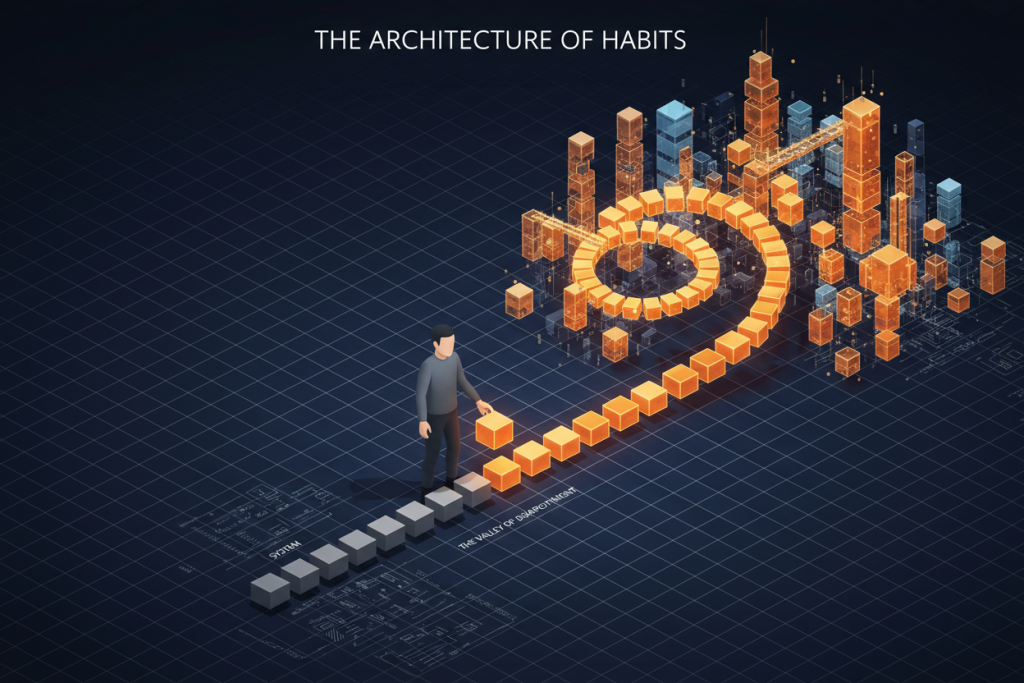

Often described using the Plateau of Latent Potential or the Valley of Disappointment is the gap between expectations and real development. Usually delayed, the most strong results in compounding procedures cause a disconnect whereby attempts seem unsuccessful for months or weeks. The ice cube metaphor helps to clarify this: an ice cube in a room at 25 degrees Fahrenheit exhibits no noticeable change when the temperature increases to 31 degrees. The phase change only happens when the temperature hits 32 degrees. This change is not a sudden innovation but rather the outcome of all the stored as latent potential prior stages of heating. Many people quit new habits too early since they have not yet passed the crucial barrier where their past efforts’ outcomes are at last accessible.

The Neurological Mechanics of the Habit Loop

Essentially acting as a mental shortcut acquired from experience to address recurring challenges with little effort, a habit is a conduct that has been repeatedly enough to become ingrained. Neurologically, this process is distinguished by a four-step feedback loop: Cue, Craving, Response, and Reward.

By anticipating a reward, the Cue sets the brain to start a behavior. Following the Craving is the motivating energy driving the behavior. One must understand that what individuals crave is the shift in inner state the habit provides, not the behavior per seethed actual conduct done is known as the Response; it varies with the level of friction and the person’s motivation. At last, the Reward satisfies the brain and helps it to recognize which behaviors are worthy of replicating.

Central to this loop is dopamine. Though usually seen as the pleasure chemical, dopamine is mostly released during the anticipation of a reward rather than its receipt. This dopamine-driven feedback loop guarantees that the craving surge drives action by the person. For habit-forming habits like social media scrolling or gambling, the brain is usually more active during the anticipation phase, hence making the addiction irresistible by means of the power of desire.

First Rule: Make it evident.

The first law of behavior change starts with awareness and environmental design focusing on the Cue. Awareness is essential as habits often get so automatic the person ceases to be aware of them. One method to regain consciousness is the Habits Scorecard, whereby one compiles daily actions and classifies them as positive (+), negative (-), or neutral (=) according to their agreement with the wanted identity.

Once aware, the person can follow the formula, I will at in, to clarify where and when a new behavior will take place using implementation intentions. Habit Stacking also uses already-established neural pathways by associating a new action with one already in place: Following, I will.

Behavior is shaped by environmental design, which acts like an unseen hand. People can greatly cut their reliance on willpower by clearly pointing out the signals of good habits and hiding the cues of bad ones. Techniques involve arranging a guitar in the middle of the living room to provoke practice or setting a book on the cushion to promote nighttime reading. Context is another strong indication; to avoid context mixing, in which competing cues (such working in bed) confound the brain’s response, people are advised to dedicate one area to one purpose.

The Second Law: Make it Appealing

By making habits unstoppable, the second law strikes the Craving. People can link a habit they require with a behavior they want by means of Temptation Bundling since expectations propel the dopamine loop. One could, for example, only listen to their preferred podcast while completing the housework otherwise eschewed.

One of the most important elements affecting the appeal of a habit is social influence. Three kinds of groups—the near (friends and family), the many (the tribe), and the powerful (those with power)—humans spontaneously copy. One of the most efficient means to keep motivated is joining a culture where the preferred behavior is the norm. One’s personal identity is greatly strengthened when a habit is a necessity for group membership.

Moreover, one might redefine challenging jobs with Motivation Rituals. Doing a quick, enjoyable activity just before a difficult habit helps the brain to connect the action with the good sensations of the rite. This moves the spotlight from the work needed to the pleasure gotten from the journey.

Third Rule: Make It Simple

The third law covers the Response by decreasing the friction connected to good habits and boosting it for bad ones. Following the Law of Least Effort, human biology tends toward the road of least resistance. The target, then, is to reduce the complexity of the task rather than boost motivation.

Initiation depends on the Two-Minute Rule: less than two minutes to carry out any fresh habit. This guideline stresses that a habit must be formed before it can be maximized. Reducing a behavior—turning run three miles into put on my running shoes, the person breaks inertia of starting. Once the action starts, continuing becomes far simpler.

Environmental Priming helps to get the environment ready for forthcoming activities, hence easing behavior. Setting out gym attires the night before or arranging nutritious lunch components, for instance, eliminates the micro-frictions that usually derail decision-making in the moment. Using Commitment Devices, choices made now that lock in future conduct, ensure adherence otherwise. Examples of using present goals to limit future negative decisions include deleting social media applications during work hours or prepaying for a class.

The Fourth Law: Make It Fulfill

Immediate reinforcement guaranteed by the last rule helps to reinforce a habit. In an environment where short-term incentives were given more weight than long-run advantages, the human brain developed. As a result, the benefits of several good behaviors (health, financial security) are sometimes too far away to give enough motivation now.

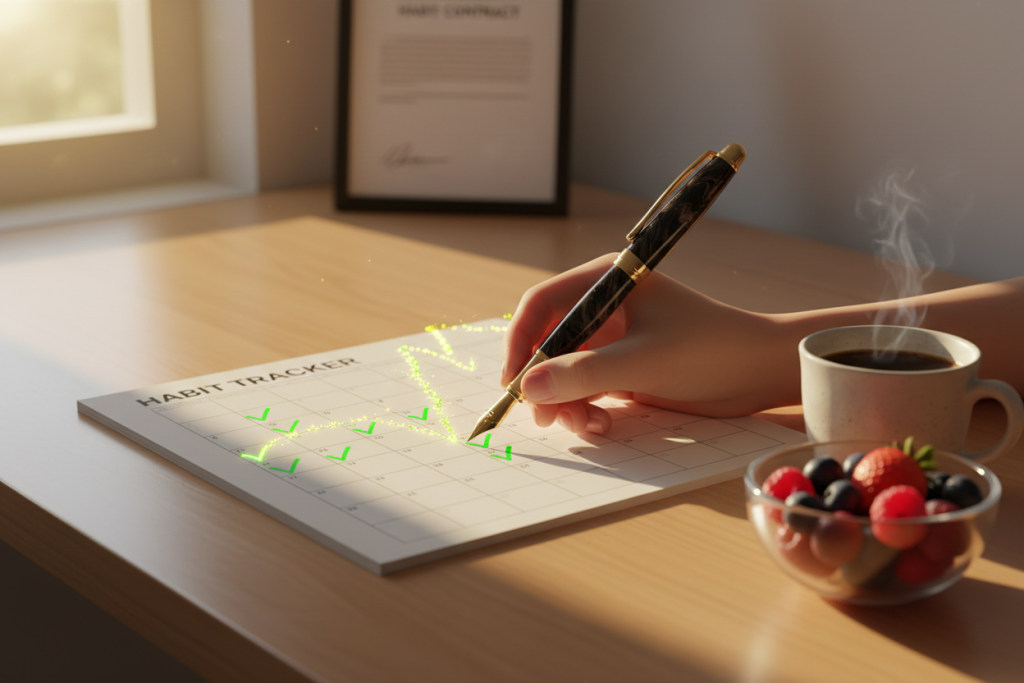

People need to produce instant gratification to fix this. One of the main instruments for this goal is habit tracking. Visually rewarding the brain’s need for completion and advancement comes from calendar recording of development or using an appeaser miss twice is the first guiding principle of tracking. Missing a habit once is accidental; missing it twice signals the beginning of a new one.

Adding an extra degree of accountability, the Habit Contract specifies a punishment right away for failure. An individual declares their commitment and agrees to a certain penalty—such a fine—in a habit contract should they fail to adhere. An Accountability Partner who sees to it that the penalty is carried out signs this agreement. This approach increases the social cost of failure, therefore highlighting in the near term the long-term advantages of the habit.

Implementation in Life Design and Workplaces

The ideas of atomic habits are directly relevant to workplaces. In the office, motion—planning and strategizing that feels productive yet yields no result—rather than action often obstructs productivity. Using the four laws helps teams to eliminate process friction, automate administrative duties, and create a culture of ongoing improvement.

- Make it apparent: Pointing-and-Calling can be used for safety measures or set explicit implementation goals for extended work hours.

- Make it allure: Create a tribe wherein excellence is the standard, then employ temptation bundling for ordinary chores like expense reporting.

- Make it Simple: Deal with little emails right away using the two-minute rule and prepare the environment by arranging digital files for easy access.

- Provide instant comments on progress by using visual habit trackers for team objectives or OKRs (Objectives and Key Results).

Taking the Next Step: Your Handbook of Permanent Transformation

Available for purchase on Amazon, Atomic Habits is intended for those ready to go beyond theoretical knowledge and start creating their own systems of development. For anybody wanting success and habit-building, it’s touted as a must-pick-up and a vital resource. The whole text acts as a manual for great personal transformation that may be consulted throughout your life path by giving the perfect route to becoming the greatest version of yourself.

Finally, the transforming force of habits lies in the regular application of modest adjustments rather than in large gestures. People can use the compound interest of self-improvement to create a life of ongoing development by changing their attention from outcomes to identity and from objectives to systems. Daily habits generate success; once-in-a-lifetime changes do not. The secret of long-lasting change is to pay more attention to one’s present path than to current outcomes.